The turntable, that elegant machine центральным (tsentral'nym - central) to our vinyl devotion, didn't spring into existence fully formed. It's the culmination of nearly 150 years of brilliant innovation, fierce competition, and an unwavering human desire to capture and replay sound. Understanding this evolution, from the earliest mechanical marvels to today's precision instruments, deepens our appreciation for the technology we use and the rich history of recorded music itself.

This journey is not just a dry recitation of dates and inventions; it's a story of how humanity learned to etch sound onto physical media and then, with ever-increasing fidelity, bring it back to life. It’s a narrative that resonates with the core mission we embrace at XJ-HOME: to celebrate and enhance the profound connection between music, technology, and the listener.

Part 1: The Dawn of Recorded Sound - Mechanical Marvels

The late 19th century was a hotbed of invention, and the quest to record and reproduce sound was a significant frontier.

-

Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville's Phonautograph (1857): Though it couldn't play back sound, Scott's device was the first to visually record sound waves, tracing them onto soot-covered paper. It was a crucial conceptual leap, proving sound could be transcribed.

-

Thomas Edison's Phonograph (1877): This was the breakthrough. Edison, working on a telegraph repeater, stumbled upon a method to record and reproduce sound. His first phonograph used a stylus to indent sound waves onto a cylinder wrapped in tinfoil. The playback was crude, the tinfoil fragile, but for the first time, a recorded human voice ("Mary Had a Little Lamb") could be played back. It was pure magic.

-

Chichester Bell and Charles Sumner Tainter's Graphophone (1886): Working under Alexander Graham Bell's Volta Laboratory, Bell and Tainter improved upon Edison's design by using wax cylinders instead of tinfoil and a floating stylus instead of a rigid one. This offered better sound quality and longer recording times.

-

Emile Berliner's Gramophone (1887): This marked a pivotal shift. Berliner introduced flat discs (initially glass, then zinc, then a shellac-based compound) instead of cylinders. His system used lateral (side-to-side) groove modulation rather than vertical (hill-and-dale) cuts. Critically, discs were far easier and cheaper to mass-produce via a stamping process from a master. This innovation laid the groundwork for the record industry as we know it. For a visual journey through these early machines, the EMI Archive Trust offers fascinating glimpses into sound recording history.

These early machines were entirely acoustic and mechanical. Sound was captured by a horn focusing sound waves onto a diaphragm, which vibrated a cutting stylus. Playback reversed the process: a stylus in the groove vibrated a diaphragm, and the sound was amplified by a large horn.

Part 2: The Acoustic Era Matures - Horns and Shellac (Early 1900s - 1920s)

Berliner's disc format, typically playing at around 78 RPM (though speeds varied), became the standard.

-

The Rise of Record Labels: Companies like Victor Talking Machine Company (later RCA Victor) and Columbia Phonograph Company emerged, signing artists and building catalogs.

-

Improvements in Materials and Mechanics: Shellac became the dominant material for records. Spring-wound motors provided more consistent playback speed than hand-cranking. Tonearms and soundboxes (the assembly holding the diaphragm and stylus) saw gradual refinements.

-

The Ubiquitous Horn: Large, often ornate horns were the "speakers" of the day. The size and shape of the horn significantly impacted the sound volume and tonal balance.

Despite improvements, the limitations were significant: frequency range was restricted, volume was limited, and surface noise from the shellac was considerable.

Part 3: The Electrical Revolution - Microphones, Amplifiers, and the Birth of Hi-Fi (1920s - 1940s)

The advent of electrical recording in the mid-1920s transformed everything.

-

Microphones: Replaced the acoustic recording horn, allowing for far more sensitive and nuanced capture of sound.

-

Vacuum Tube Amplification: Enabled the weak electrical signals from microphones to be amplified sufficiently to drive electro-mechanical cutting heads. This meant louder, more dynamic recordings.

-

Electrical Playback: Turntables began to incorporate electromagnetic pickups (cartridges) that converted the stylus's mechanical vibrations into an electrical signal. This signal was then amplified and fed to loudspeakers – a far more versatile and higher-quality solution than acoustic horns.

-

The "Battle of the Speeds":

-

33⅓ RPM LP (Long Play): Introduced by Columbia Records in 1948. Made from vinyl (polyvinyl chloride), these microgroove records offered significantly longer playing times (around 20 minutes per side) and much lower surface noise than 78s.

-

45 RPM Single: Introduced by RCA Victor in 1949. Also made of vinyl with a microgroove, these 7-inch discs were designed for single songs and featured a larger center hole, requiring an adapter.

The 78 RPM format gradually faded as LPs and 45s took over, offering better sound and convenience.

-

Part 4: The "Golden Age" of Analog and the Hi-Fi Boom (1950s - 1970s)

This era saw the refinement of technologies that define the modern high-fidelity turntable.

-

Stereophonic Sound: Commercial stereo records and playback systems arrived in the late 1950s, offering a more realistic and immersive listening experience with two distinct channels of audio. This required new stereo cartridges and cutting techniques.

-

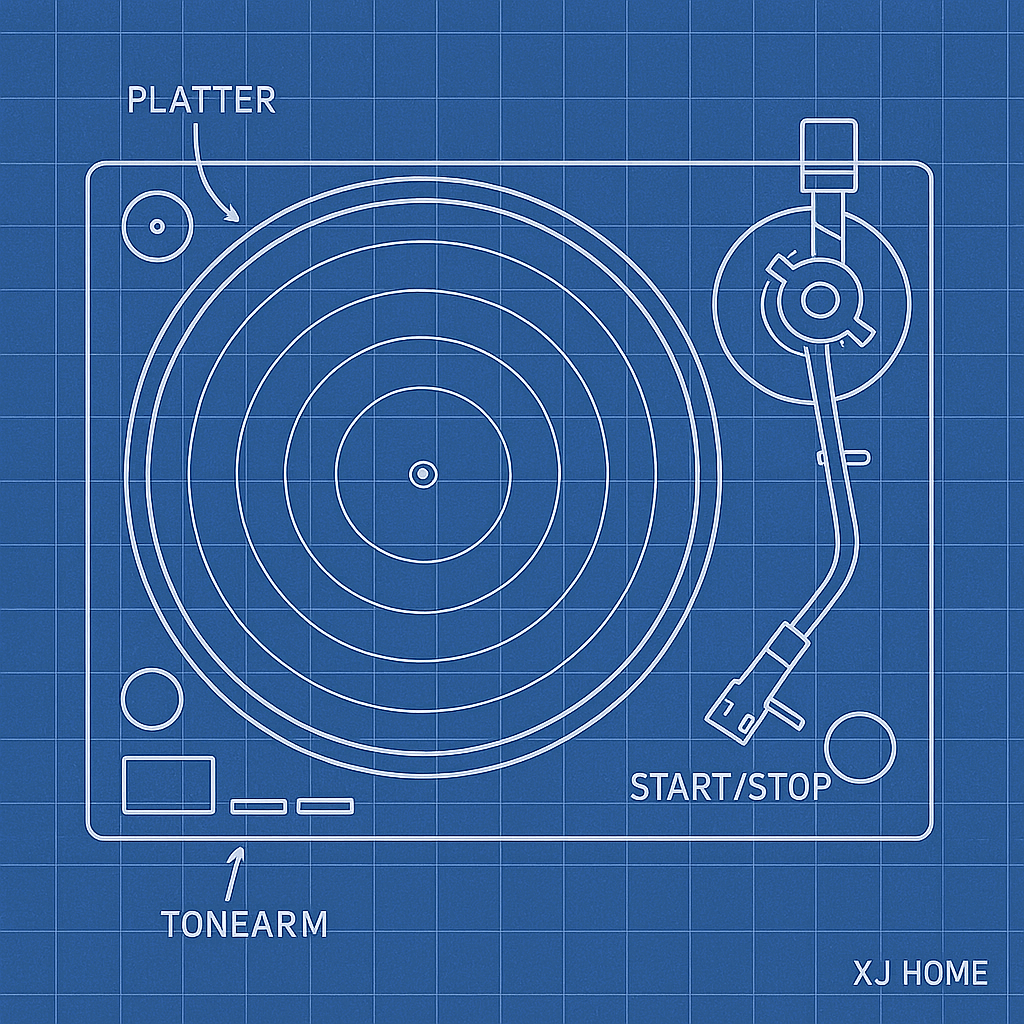

Improved Turntable Components:

-

Tonearms: Became more sophisticated, with attention paid to bearing quality, effective mass, tracking error minimization (e.g., S-shaped and J-shaped arms), and anti-skate mechanisms.

-

Cartridges: Moving Magnet (MM) and Moving Coil (MC) designs offered significantly improved frequency response, lower distortion, and better tracking ability. Diamond styli became standard.

-

Drive Systems: Belt-drive and direct-drive systems emerged as alternatives to idler-wheel drives, each offering different advantages in terms of speed stability and noise isolation. Brands like Thorens, Garrard, AR (Acoustic Research), Dual, and later Technics, Linn, and Rega became household names among audio enthusiasts.

-

-

The Rise of the Audiophile: A dedicated market emerged for high-quality audio components, with listeners actively seeking out the best possible sound reproduction. Magazines and clubs dedicated to hi-fi flourished.

Part 5: The Digital Disruption and Analog's Enduring Appeal (1980s - Present)

The introduction of the Compact Disc in the early 1980s dealt a massive blow to vinyl. For many, the CD's promise of pristine sound, no surface noise, and convenience was irresistible. Vinyl sales plummeted.

-

Analog in the Wilderness: Many mainstream manufacturers ceased turntable production. However, a dedicated core of audiophiles and smaller specialist companies kept the analog flame alive, continuing to refine turntable technology.

-

The Turntable as Instrument: Turntablism: Hip-hop DJs in the 1970s and 80s had already begun using turntables (especially the robust Technics SL-1200) not just for playback but as musical instruments, developing techniques like scratching, beat juggling, and looping. This subculture played a crucial role in keeping turntables visible and relevant.

-

The Vinyl Renaissance (Mid-2000s - Present): Against all odds, vinyl began a remarkable comeback. Reasons are multifaceted: a desire for tangible media in a digital world, perceived warmer sound quality, the appeal of large-format artwork, and a nostalgic connection for some.

-

Modern Turntable Technology: Today's turntables benefit from decades of refinement and new technologies:

-

Advanced Materials: Carbon fiber, ceramics, sophisticated alloys, and constrained-layer damping are used in plinths, platters, and tonearms to control resonance.

-

Precision Engineering: Motor control systems offer exceptional speed stability. Bearings are machined to incredibly tight tolerances.

-

Sophisticated Electronics: Outboard power supplies and advanced phono preamplifiers further enhance performance.

-

USB and Digital Integration: Some modern turntables include USB outputs for digitizing records or even Bluetooth for wireless streaming, blending analog tradition with digital convenience.

-

The XJ-HOME Perspective: Honoring the Legacy, Embracing the Future

The journey from Edison's tinfoil to a modern, high-performance turntable like those we admire at xenonjade.com is a testament to human ingenuity. Each era built upon the successes and addressed the limitations of what came before. This evolutionary spirit – the constant striving for better fidelity, for a more authentic connection to the recorded performance – is what fuels our passion.

Understanding this history enriches our appreciation for the LPs we collect and the equipment we use to play them. It reminds us that the pursuit of great sound is a long and storied tradition. For those wishing to delve even deeper into specific historical periods or technologies, the Audio Engineering Society's Journal (JAES) is an unparalleled resource for scholarly articles on audio history and technology.

The modern turntable stands on the shoulders of giants, embodying a legacy of innovation that continues to evolve, ensuring that the magic of vinyl will spin on for generations to come.

Leave a comment

All comments are moderated before being published.

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.